Spey Fly Construction

Spey fly construction was often described in historical fishing books. Early Spey flies were most often dressed on long shank hooks. In his 1846 book, Stoddart suggested using Philips and Adlington hooks for salmon fly construction. Phillips hooks were reported to be “sleek and pleasing.” Both light and heavy wire versions were manufactured. Adlington hooks were reported to have a round bend. Early steel fish hooks were usually blind eye hooks. A leader was directly attached to the hook. A loop of gut was most often attached to early salmon fly hooks.

Stoddart suggested – “As regards the salmon fly, one great improvement, of recent date, consists in the substitution, as a mode of attaching it to the line, of a small loop or eyehole of gut at the head or shank-end of the hook, instead of a full length of the same material. This loop, as in the case of the length in question, may be formed either of triple or of single gut, according to the size of the wire.”

Some Autumn Days on the Spey

R.B Marston in an article titled “Some Autumn Days on the Spey” indicated “Mr. Brown, of George-street, Aberdeen, who makes these and all other standard salmon flies to perfection”. The article went on to report –

“To describe the dressing of a Spey fly generally, and not any pattern in particular, I think the clearest plan would be to follow the tabulated form used in the Badminton volume on “Fishing,” when describing the ordinary standard flies, which would show where these peculiar constructions differ in their respective parts from the well known standards. Thus, an ordinary fancy fly, with say a wool or fur body, would have all the parts which are indicated in italics, whereas the Spey fly takes only those that are described, viz.-

Tag –

None.

Tail –

None.

Butt –

None

Body –

Usually consists of common wool mixed or dyed to the shade of colour required, and wrapped round the hook tightly. There is no picking out or “furriness” about the body of a Spey fly; and as it is begun on the shank in a line with the point of the hook, it has a dumpy disproportionate appearance.

Ribbed –

There are invariably three tinsels down the body—a flat, and two threads; one of the threads silver, the other gold (on some patterns these are replaced by coloured silk threads). The flat and one thread is wound round the body in three turns, room being left for the second thread, which is not wound until after the hackle is put on. “

Hackle –

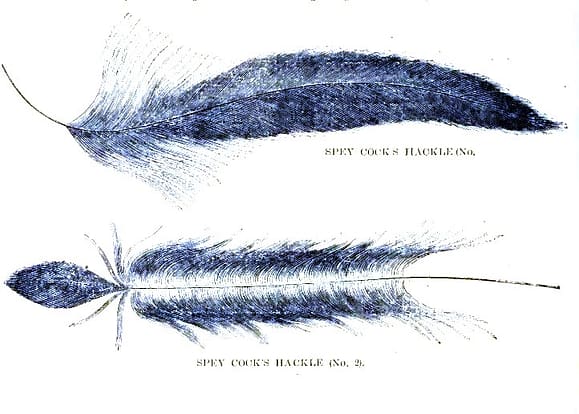

The hackle is perhaps the most distinguishing feature of the Spey fly, and the greatest puzzle both to amateur and professional fly-tiers. It is not, properly speaking, a hackle, but is taken off that part of the cock which might be called the ‘saddle,’ or near the tail.

The best feathers hang with a graceful curve from the root of the tail down the side of it, and when the fibres are extended to right angles with the stem, they will be found to be of equal length from butt to tip—not tapering as in a hackle. The feather thus described is also very soft in fibre, and when dressed on the fly, has a very different appearance to the ordinary cock’s hackle, and a very different effect in the water. Now as the hackle of the Spey fly differs from ordinary hackles, so does the manner of putting it on.

The ordinary standard fly…

has the hackle tied in, or begun, at the small tip or point. The Spey fly has it tied in, or begun, at the butt or thick end of the stem. Having cleaned off the downiest part of the fibre at the butt-end, and left just a little of the gray (a sort of half ‘down,’ half fibre), and having seen that the fibre is long enough to extend about half-an-inch beyond the bend of the hook— the stem is tied in at the very commencement of the body, along with the tinsels.

When the two tinsels—a flat and a thread—have been wound to the right hand, the hackle is taken and wound to the left hand. The tinsel is then wound to the right, parallel with the other two, and across the hackle stem at every turn. When fixed, a needle is required to relieve those fibres of the hackle which may have been tied down by the crossing tinsel. The fly is then ready for the –

Throat Hackle –

Throat Hackle, which is generally teal, wound in the ordinary fashion.

Wings –

Wings are generally two double strips of brown mallard, not extending much above the length of the body, and set on to permit of the natural curve of the feather. The two wings sit quite apart, and are put on separately.”

Body materials

Knox indicated the body of the original Spey flies was “composed of Berlin wool.” Berlin wool came from Merino sheep. The wool would readily absorb aniline dyes developed in the mid-1850’s and were available in a variety of colors. In the nineteenth century the wool was combed (worsted), and spun. Later it was taken to Berlin where it was dyed and sold. The wool was softer and separated more easily into strands than other types of wool. Production of Berlin wool ended in the 1930’s. Although Merino wool yarn is still readily available today in a variety of colors.

Stoddard had earlier suggested pig’s wool could be substituted for the mohair in his Spey flies No.1 and 2. Pigs wool is an actual wool from pigs and may have come from very early hog breeds or wild boars. Notwithstanding, a more recent pig breed is the Mangalica, a Hungarian domestic pig. It was developed in the mid-19th century and grows a thick woolly coat similar to that of a sheep. It is coarser and crinklier that other types of wools. Pigs wool in several dyed colors is available from online suppliers of classic fly tying materials but is expensive.

Tinsel

Original Spey style flies also incorporated several oval, flat tinsel and sometimes floss ribbings wound around the body. In some patterns, one of the smaller oval tinsels was wound counter and after the body hackle was wrapped to help secure and protect it from breaking. Today, both varnished metal and mylar flat and oval tinsels are readily available.

Body Hackle

A unique Spey fly characteristic is a feather palmered over the body. Feathers from the sides of the tail of a “Spey cock”, a type of chicken raised near the River Spey were often used. The feather was taken from the sides of the chicken tail and ranged in color from brown, grey and black. Although the Spey cock is thought to have disappeared many years ago, selected Schlappen feathers appear to be very similar. Likewise they can be used as a substitute for the Spey cock hackle.

A few Spey patterns were also dressed with black or grey heron feathers. These were likely from the European Grey Heron Ardea cinerea. In all patterns the feather was palmered “along the body of the fly” according to Knox. It should be noted the body hackle was tied in at the butt or thick end of the feather rather than the tip. This helped make the fibers stand out from the body.

in The Fishing Gazette Volume XXII, 1891, edited by R.B. Marston

Stoddard’s Spey Flies

Although Stoddard’s Spey flies No.1 and 2 did not include a shoulder hackle, other’s did. Both Knox’s old Spey patterns and Marston’s descriptions called for a teal or guinea hen feather. It was wound as a shoulder hackle in the “ordinary fashion.”

As mentioned, paired brown mottled flank feathers from a drake mallard were used as wings. In his writings, Stoddart suggested – “In the dressing of Scottish salmon flies, there are two modes of laying on the wings, before fastening. They may be set either horizontally, the one with the other, as they are placed in the moth, the bee, common house-fly, and various other insects, or in such a manner that they shall correspond, in point of position, with the wings of the butterfly and of the generality of water-ephemerse, that is, with their inner sides turned face to face, at a considerable angle of elevation from the body.”.

The latter method of winging is not often depicted on pictures of early Spey flies. The advantage of using bronze mallard flank feathers is its ability to retain shape. In addition the individual fibers do not separate when secured to the hook. The thread is tied in over the grey portion at the base of the slip where attached to the stem. This helps to retain their shape.

Lady Caroline

One early Spey fly that has gained lasting fame for steelhead is the Lady Caroline. This somber colored pattern continues to be popular and makes a good caddis imitation for summer steelhead. Other original Spey flies are occasionally seen in anglers fly boxes, usually for winter steelhead. These include the orange body Carron and Black Heron.

Modern Spey Flies

A few modern Spey flies for California steelhead have been created following the original Spey style. These included the Clouseau and Solar Flare created by Sacramento fly tyer Jim Zeck. These patterns also incorporate the use of Ultraviolet materials in their construction. Our new book, California Winter Steelhead provides information about the Spey fly. Color photographs of several original and modern Spey flies for winter steelhead fishing are also included.

Furthermore Spey flies will continue to have a place in winter steelhead fly boxes. In addition, Northwest feather wing patterns created by Glasso and others will also remain popular and effective. New patterns are continually being created and todays steelhead fly tyers are only limited by their imagination and creativity. In the words of Scottish angler Thomas Tod Stoddart – “Let your supply of flies be small and fresh, and the means of replenishing it always at hand; thus, you will save useless expense, and remedy interminable confusion.”

Collections of classical and modern Spey flies and Northwest feather wing flies are for sale under Assorted Fly Boxes.

Greatest Spey Flies Ever Tied – Discover Early History Here – Part 1